Ten warships in total, including three destroyers, an amphibious assault ship, a guided-missile cruiser, and a nuclear-powered submarine, along with some 10,000 troops. The Navy's deployment, ordered by Donald Trump in August in the area of influence of the U.S. Navy's Southern Command, has few precedents in the Caribbean and an equally unusual enemy: the Venezuelan drug cartels.

A couple of weeks ago, the president announced to Congress, without the opportunity for debate, his decision that the country has entered a war against them. For now, the casualty report is more modest than such a show of power, no less than the mobilization of 14% of the United States' naval force deployed around the world, might lead one to believe: four boats allegedly sent by drug cartels, which Washington accuses of drug trafficking, in four extrajudicial operations for which the authorities have offered no evidence other than videos of the moments in which they exploded. In these operations, the Army has killed at least 21 people, four of whom Bogotá claims as Colombian citizens.

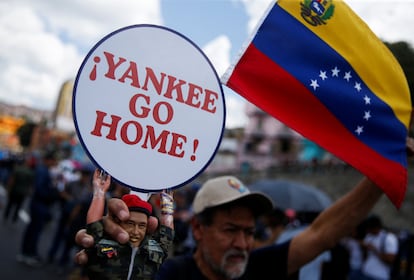

Trump's offensive in the Caribbean has heightened tensions in the region, as well as suspicions that this is more than just an attempt to revive the war on drugs that once defined Washington's policy in its backyard."This isn't about ending drug trafficking, but rather about bringing about regime change—a deeply corrupt and criminal regime—and making Washington pay off," Christopher Sabatini, senior researcher for Latin America at Chatham House, explained in a telephone conversation on Friday.

Sabatini defined the White House strategy as “shotgun diplomacy.” The goal would be “to intimidate the officials and military personnel surrounding Maduro into letting him fall. It means abandoning the same costly peaceful processes, by the way, that have earned [opposition leader] María Corina Machado the Nobel Peace Prize.” Juan González, the Biden administration’s Latin America strongman, agreed with that assessment this week: “It looks, acts, and speaks like an attempt at regime change.”

Second phase

The first phase of this offensive is the four extrajudicial military operations that Trump and his Secretary of Defense, Pete Hegseth, have been reporting on social media. For Sabatini, they are"worrying" for three reasons: "They expand the president's executive power by inventing a new threat, that of narcoterrorism, which requires an armed response; they ignore due process by blowing up vessels without providing evidence of the crew or cargo; and they exaggerate Venezuela's role in drug trafficking to the United States, because there is no evidence that fentanyl is produced there and, according to official statistics, only 5% of cocaine comes from there," explains the expert, who adds that these vessels"do not have the autonomy" to reach the US coast.

"They're probably headed somewhere in between. Which one? We don't know," he added. These doubts haven't prevented Trump's argument—which included several cartels, including the Venezuelan Tren de Aragua, on the State Department's list of"terrorist organizations" in February as a preliminary step toward declaring war on them—from gaining popularity in recent days with the idea that each of these boats is carrying enough narcotics to kill "25,000 or 50,000 Americans."

"There's a lot of theater in these attacks, and in the military deployment—even a nuclear submarine!" says Moisés Naím, a distinguished fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for Peace and one of the most influential Venezuelans in Washington."It's like a staged scene, a context that serves to justify subsequent actions."

Trump himself admitted last Sunday that something would come next: after the boats, the campaign, which he considered"successful," is ready to enter "phase two." "We'll see what that entails," he said, and then added, for the sake of clarification, that it would continue on land."It's impossible to know what form [that operation] will take. Perhaps it will focus on eliminating criminal networks and sites in Venezuela; ports or airports involved in drug trafficking," Sabatini believes."It won't be an armed invasion, with thousands of soldiers, as some would like," Naim thinks."It will be surgical, selective, well-aimed, technological. I just hope that Machado's Nobel Prize changes their minds [Trump and his followers]."

In an interview with EL PAÍS on Friday, the newly elected president, who leads an opposition that, according to most of the international community, was robbed of last year's elections by Chavismo, declared:"We are facing the real possibility that Venezuela will truly liberate itself and move toward a transition that will be orderly, because 90% of the population wants the same thing. Don't tell us this could be Libya, Afghanistan, or Iraq; this has nothing to do with it," she said, referring to other disastrous US adventures abroad—a pattern Trump promised during his campaign not to repeat.

Among the experts consulted in Washington, the possibility of the clean transition that Machado takes for granted is not so clear. There is also a widespread belief that the Trump administration is trying to finish what it started in 2019.

“And it's practically the same actors doing it. Besides the president, there's Marco Rubio,” warns Alexander Main, director of international relations at the Center for Economic and Policy Research. Back then, Rubio was a senator with the ability to whisper in Trump's ear about Latin America. Today, he has positioned himself as one of the most powerful men in the White House in his dual role as Secretary of State and National Security Advisor. “The two were at odds during the 2016 campaign, but then reached a compromise: Rubio would help him mobilize Florida Republicans in exchange for support for his vision for [what in Washington they call] the Western Hemisphere,” says Main.

During his first administration, pressure came first through the imposition of sanctions, and then through support for Juan Guaidó, in an operation that Sabatini defines as"that fanciful idea of creating a parallel legitimate government." "I think Trump is still embarrassed about having invited him [Guaidó] to the State of the Union address in 2019," he adds.

So, Washington failed to calculate that something like this would cause the Chavista regime to collapse like a house of cards. Main fears that the corresponding lessons were not learned."I think Rubio and Trump are once again confident that a brief military intervention will bring down Maduro. When the consequences of something like this are unpredictable. Most Venezuelans, even if they are fed up with their president, are not in favor of a US intervention."

Last week, in another demonstration of an aggressive foreign policy that has given him mixed results in resolving the wars in Gaza and Ukraine, Trump ordered the suspension of all diplomatic contacts with Venezuela, after months in which Maduro, who is going through his most difficult days, tried unsuccessfully to appease Washington by offering a dominant stake in the South American country's oil and other mineral resources, The New York Times revealed this Friday. The Venezuelan president also promised to distance himself commercially from China, Russia and Iran, his partners until now, who have provided him with money he needs to mitigate the impact of international sanctions.

The White House rejected the proposal. Not only that: in August, it doubled the reward, up to $50 million, offered for any information leading to the arrest of Maduro, whom Washington considers the leader of a narco-state.

The order to cut off diplomacy at its root was directed primarily at Richard Grenell, Trump's envoy in the region, who shares a certain rapport with Jorge Rodríguez, Maduro's main political operative. According to sources close to the Chavista high command, the Bolivarian leader was not as submissive in that negotiation as Washington would have us believe. Be that as it may, the diplomatic channel is broken, except for the part where Venezuela continues to receive flights of deported migrants from the United States: some 10,000 since February.

On the streets of Caracas, accustomed to 25 years of Chavista uncertainty, the same doubts are heard as in the offices of Washington: no one knows what the extraordinary US naval mobilization will bring. Or perhaps it's because most people prefer not to comment on their compatriot's Nobel Prize either. It's better not to get into trouble.

Chavismo, for its part, has the Armed Forces busy with almost weekly military exercises and has ordered all public institutions to decorate buildings and offices with Christmas decorations, which makes it difficult to put adjectives to the atmosphere in the country. Meanwhile, Maduro maintains his agenda: he inaugurates hospitals, signs a decree of a state of emergency due to external shock (which gives him total powers that he already holds) and has even received an honorary doctorate.

Around public buildings, corners have been reinforced with pairs of soldiers in riot gear. The security rings around Miraflores Palace have been extended. And at the main access to the capital from Maiquetía International Airport, concrete barriers have been deployed, which can be moved in case it is necessary to"block the enemy's path," according to a soldier who spoke to official media.

But it's in the coastal areas where the greatest military mobilization is taking place. In Zulia and Sucre, which are home to major drug distribution centers, fear of drone attacks is spreading."There's fear in the streets, people are waiting for something," says a resident of the eastern coast of Lake Maracaibo by phone. Nervous shopping (and stockpiling of food) is the immediate reflection in Venezuela of the escalating political conflict. Since the years of long lines to buy food, it has become a prophylactic habit. Although amid so much war tension, daily survival, given the rising prices and the deteriorating economy, is more of a concern on a day-to-day basis, for now.

And in the midst of this scenario, there are no signs that Maduro is willing to relinquish power in the context of a negotiation, according to the aforementioned source close to Chavismo. It's a movement that has made resistance its way of life in a country that has experienced devastating economic crises, on par with a country at war, and that survives international sanctions as best it can. The United States fleet anchored in the Caribbean is a real threat, but Maduro and his followers seem willing to push the situation to the limit, waiting to see if Trump dares to take a definitive step.

He doesn’t have all the time in the world for that either, while critical voices against his cannonball diplomacy are growing in Washington. On Wednesday, the Senate rejected in a close vote (48-51) an initiative by Democrats Adam Schiff and Tim Kaine that would have halted attacks in the Caribbean before the 60-day deadline that Trump gave himself under the War Powers Act of 1973 expires. “So by the beginning of November, he would have to stop those military operations, if he decides to continue without congressional authorization by attacking ships, then he would be breaking the law,” warns Katherine Yon Ebright, of the Brennan Center for Justice, associated with New York University.

This rule, the expert adds, also allows the president to request an additional 30 days to withdraw U.S. forces from the zone of hostilities. That is, from those waters where an extraordinary Navy deployment is now taking place, unprecedented in recent Caribbean history.