Ukraine has been fighting off Russian drones for years and have built up tested tactics for detecting and destroying Shahed drones – the explosive-toting aircraft that for the first time ever penetrated NATO airspace on Wednesday. Here are four key Ukrainian lessons learned in the anti-Shahed campaign.

1. There really is no substitute for actual combat experience

According to Ukrainian Air force counts, Russian forces sent about 12,000 of the Iran-designed aircraft each carrying a 50-90 kg warhead into Ukrainian airspace in 2024. In 2025 the count to date is about 15,000 launches in strikes taking place daily.

On a routine day Ukrainian air defenses have to handle 70-100 aircraft. In a big raid taking place two or three times a month the count might be 400-500 Shaheds accompanied by one or two dozen missiles.

A massive attack takes place about once a month with 600-800 drones and 50+ missiles. This makes Ukraine’s air defence command the world’s most practiced air defense command, in wartime, on Earth.

The Tuesday attack that saw 19 Shahed drones breach NATO airspace was, by Ukrainian wartime standards, a big attack. On the Ukrainian side of the Polish border, that day, Ukrainian air defenses observed 415 Russian drones and 43 Russian cruise missiles, and shot down 386 drones and 27 cruise missiles.

By Ukrainian wartime standards that was above par for successful drone engagements (93 percent, usually the Ukrainians claim 80-85 percent drone kills); and somewhat below par for successful missile engagements (63 percent, usually the Ukrainians claim 75-80 percent cruise missile kills.)

NATO’s effort to contain 19 drones that made their way through Ukrainian airspace, deep into Polish airspace, was less successful: four drones shot down, reportedly by fighter aircraft firing expensive air-to-air missiles. A 24 percent successful interception rate would be, by Ukrainian wartime standards, shockingly poor performance and probable grounds for sacking the entire regional air defense command leadership.

But it would not be fair to apply that standard to the NATO officers and men dealing with a wartime drone strike for the first time in their lives that night.

Almost certainly, NATO’s peacetime stance of avoiding escalation even at the expense of effective air defense made intercepting the encroaching drones more difficult. Almost certainly, on Tuesday night NATO field commanders and combat pilots had to make sure a missile shot at a Russian drone might not fly into Belarus, Kaliningrad or a Polish inhabited area by accident.

During the night’s air battle, generals not normally involved in tactical air defense decision-making (other than in simulations and exercises) were faced with taking responsibility for approving the first-ever combat launches of air-to-air missiles in NATO airspace.

In Ukraine, during a Russian drone raid, air raid early warnings are common hours before the actual strike, usually when Russian bombers armed with missiles are detected flying to launch sites in central Russia or over the Caspian Sea.

Less frequently, Russian technicians are spotted placing drones onto launch racks in Crimea or in southwest Russia but, once the Russian missiles and drones take flight, Ukraine’s air defense command historically has had a green light to intercept and destroy anything in the air.

2. In Ukraine, it’s not just the military searching for Russian drones

Since Russia’s Feb. 2022 invasion Ukraine’s air defense command has tracked practically all Russia aircraft within hundreds of kilometers of Ukraine’s borders, thanks to extensive intelligence-sharing with NATO air watch networks and, to a lesser extent, intelligence-sharing with US-run satellite networks.

Ukraine’s army has a lot of air watch capacity of its own including domestic and imported long-range air defense systems like the US-made Patriot missile and the French/Italian SAMP-T missile, and more recently AEW&C planes donated by Sweden. On its eastern edge, NATO deploys exactly the same equipment, and a lot more of it.

But NATO does not have anything like Ukraine’s innovative Sky Watch system, which by formal description is a national network of acoustic sensors data-linked to a central fusion cell enabling the location and tracking of incoming aircraft in real time.

In practical terms, what the Ukrainians did starting in 2022 was place thousands of run-of-the-mill mobile phones at listening posts across the country (a common site was literally a telephone pole), rig the phone with a power source, set it to listen 24/7, and then use computers crunching the relative strength of engine sound of a drone (strikingly similar to a lawnmower) to triangulate the drone’s location and direction.

Two Ukrainian engineers reportedly came up with the idea and tested it in their garage in 2022; by mid-2025 the concept had turned out to be scaleable and the Ukrainian government turned out more than willing to invest in air defense technology used by no army on earth.

Military analysts usually estimate Ukraine operates between 10,000-15,000 sensors nation-wide, and cost estimates range from $5-$54 million. A single top-of-the-line F-35 jet costs $80-100 million. A single Patriot missile system costs about $1 billion.

Complementing Sky Watch, the Ukrainian government has organized a nationwide network of air wardens, for the most part retired military or local officials in remote villages, into a detection web calling in spots of aircraft either seen or heard, and possible direction. The monitors, many volunteers, number in the thousands.

Civilians add data flowing in to Ukraine’s air defense command by calling or texting in much the same information directly to the local air watch office, or by contacting a nearby air defense unit and telling the troops.

In the early days of the Russian bombardment campaign the information flood was chaotic and seemed to foster panic by making one observation seem like many.

But by early 2024 dedicated Telegram channels, both on national and local levels had become the default location for both the military and general public to learn what about what civilians were seeing and hearing.

During most Russian strikes, in 2025, reports come fast and accurately enough for anyone with mobile data connection to track incoming aircraft in close to real time.

3. In Ukraine, taking out a Russian Shahed isn’t a one weapon/one specialist job

In the early days of the Russian Shahed drone bombardment the Ukrainians quickly learned that even if an air defense missile is perfectly designed to knock down an aircraft like a Shahed, it often isn’t cost effective.

The Shahed itself according to Russian news reports costs the Kremlin $50-75,000 an aircraft depending on whether it’s Iran- or Russia-made and the type of electronics aboard. Along with Shaheds Russia produces and launches thousands of decoy drones, called a Gerber, which look like an explosive-toting Shahed on radar but costs about $10,000.

Assuming the White House is allowing deliveries, which has not always been the case for Ukraine, a single top-of-the-line US-made Patriot interceptor missile costs $4-6 million depending on the type. Lighter but still sophisticated missiles like the NATO-standard AAMRAM or the Soviet-era R-77 (NATO reporting name: AA-12 Adder) could cost from half a million to a million a piece.

According to some news reports one of the very advanced missile used by a Dutch F-35 pilot to defend NATO airspace over Poland cost an unverified $2.8 million – more than 500 times the cost of the Shahed drone the NATO missile shot down.

Strapped for cash and forced to defend an airspace about eight times bigger than the NATO airspace violated by the Russian war drones on Wednesday, Ukraine has had little choice but to use not the very best tool possible to destroy Russian drones, but whatever is available.

Ukraine has small numbers of fighter planes donated by France, Netherlands, Belgium, Norway and Denmark, and according to Ukraine’s air defense command they regularly fly intercept missions against incoming Shaheds. Some pilots have become aces hunting the Russian unmanned aircraft, but, air-to-air missiles are expensive and at least one aircraft, possibly two, have been lost flying too close to an exploding Shahed.

Ukraine’s military defends critical sites like major infrastructure, central government institutions and arms manufacturing with a combination of ground-launched anti-aircraft missiles and military auto-cannon. Germany’s Gephard anti-aircraft system – a tracked cannon system obsolete by NATO standards – has been a stand-out thanks to its very high rate of fire and excellent radar.

At those sites jamming on wavelengths used by the Shahed to communicate with its operators back in Russia, often by Starlink, is common in Ukraine. In major Ukrainian cities GPS navigation systems typically do not work near major targets – Ukrainian motorists generally accept it as a necessary inconvenience.

But also, as tracking of the incoming Shaheds has improved, Ukrainian air defense planners have fielded thousands of local gun/truck platforms, usually a pickup truck mounted with a heavy machine gun, that are manned by National Guardsmen who work civilian jobs during the day but like firemen rush to a firing point where the tracking command expects drones might pass.

In rural regions regularly overflown by Shaheds machine gun teams are a regular fixture, somewhat like volunteer firefighters during peacetime.

The Ukrainians use the same mobility tactic with military gunners operating hand-held anti-aircraft missiles designed primarily to take out attack helicopters over a ground battle, whom dispatchers deploy in the path of a detected Shahed stream.

But even this small missiles can cost more than a Shahed, and several times more than a Shahed decoy.

Like with the mobile gun and missile teams, the Ukrainians deploy vehicle-mounted jammers into the path of incoming drones. Hard information is scarce on the technologies involved.

Ukrainian military analysts have reported some jammers attack the drone’s communication link or its satellite navigation, while others transmit false data, a technology called spoofing, that push the drone off course.

There are reports of the Ukrainians have built a belt or belts of stationary spoofer transmitters in southern and eastern Ukraine, and near Pokrova, but that is not confirmed.

4. In Ukraine, tech development is bottom up and the future is interceptor drones

Ukraine never set out to make interceptor drones, is just worked out that way.

In mid-2023 Ukrainian troops were struggling against massive Russian artillery shell advantage powered by squadrons of Russian observation drones calling down shell strikes.

As an emergency tactic, Ukrainian FPV drone pilots normally hunting Russian tanks and armored personnel carriers modified their aircraft to fly higher and faster, and attempts to ram the Russian observation drones began.

Furious experimentation and development followed in the new drone vs. drone air war, and not with glitches.

Drones deploying nets or firing shotguns were test and found not so useful. Russian observation drones started carrying rearward-facing cameras to spot a rammer, the Ukrainian counter was to make their drones faster so the Russian pilot had less time to dodge.

Both sides experimented with interceptor drones – not much advantage and costlier to build. But by mid-2024 many Ukrainian combat brigades had at least a few drones designed to be flown to attack another drone over the battlefield.

In late 2024, as Russia ramped up its Shahed production, Ukrainian drone manufacturers turned to developing a counter, at the start by modifying already-existing battlefield anti-drone drones for attacks on Shaheds, which flew faster and usually lower than observation drones.

One solution was the jet-powered Mongoose, developed by a Odesa-based designed group.: In July 2025, the Ukrainian air force credited mobile fire groups operating Mongoose drones with 20-30 Shaheds in a single night.

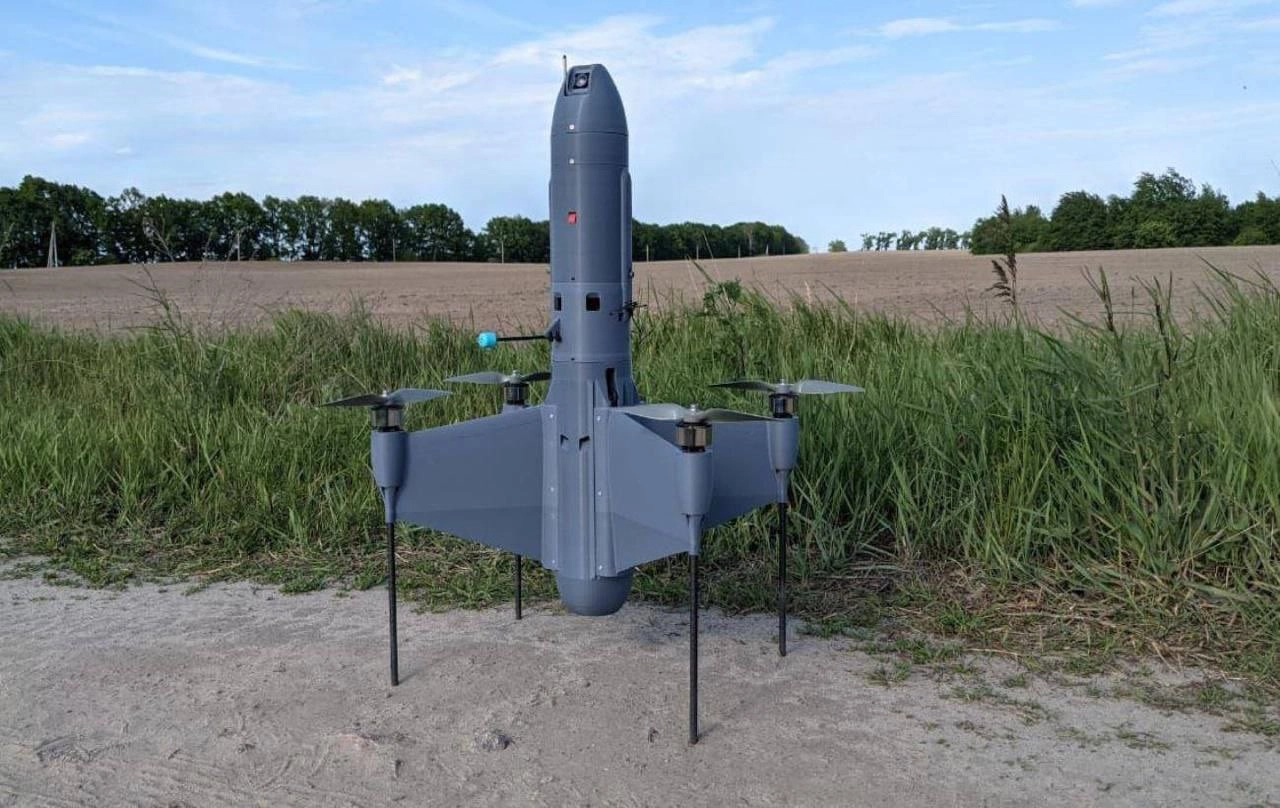

The propeller-driven Hornet, a fast, agile drone equipped with AI-guided targeting, swarm capacity and jamming modules, has been developed by a Kyiv-based company called Center for Defense and Electronic Technologies). The design company Tenbris came up with a stubby, cheap-to-make drone called a Bahnet (Ukrainian: Багнет = Bayonet)

Production went forward. On Sept. 7, 2025, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy in a national television video address credited interceptor drones with the successful downing of 150 Russian long-range attack and decoy drones out of a massive air raid for that day consisting of 810 Shahed drones. It had taken less than a year to go from a non-existent weapon to an effective air defense system proving its worth in a real war.

Ukraine needs to increase its interceptor drone production so that any Shahed swarm is met and attacked by an interceptor swarm, Zelensky said.

In NATO forces, Germany, Poland, Britain, Netherlands, France and Finland have tested interceptor drones experimentally. Germany and Poland have produced a few hundred each and Finland a few thousand, but not all are interceptors.

Currently the NATO strategy on interceptor drones is a project called European Sky Shield Initiative which will deliver about 8,000 drones to the Atlantic Alliance by 2029.

On Wednesday, in the wake of the Russian strike against Poland, Zelensky said Ukraine was happy to share its air defense experience and technology with NATO, if NATO is interested.

Ukraine has unveiled the “Bayonet” drone interceptor to target Russian Shahed and Geran drones, Militarnyi reports. It can fly up to 16,000 ft (5 km) in altitude, 40 km range, and match the Shahed’s 220–250 kph speed. Features include automatic takeoff/return, visual target lock with optimal interception course, and planned upgrades for full autonomous guidance plus a network allowing one operator to control 15 interceptors from three stations.